The “Big 3” distributors – Performance Food Group, Sysco, and US Foods -collectively reported 12% year-over-year (YOY) price inflation in their most recent quarterly results, a rate not seen since the early 1980s. These staggering increases occurred in spite of the fact that they have inflation buffers built into purchasing agreements and supply major chain customers with commodity hedges and contract protections of their own. So one thing can be sure, product price/cost inflation is passing through to “unprotected” independent operators.

The average restaurant (including chains) earns a 3-6% operating profit, modest considering the difficulty of all that is entailed. And whether they fare better or worse, they all have something in common: Cost of Goods Sold (COGS). COGS combines with labor expense to comprise “Prime Cost,” ranging from 50-70%, with quick service restaurants (QSRs) skewing low and full service restaurants (FSRs) high. And since nearly all QSRs are chains, that leaves FSRs comprising the majority of independent restaurants.

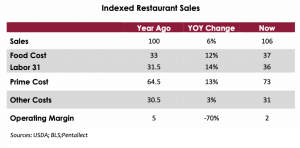

The USDA’s recent accounting of Food Away-from-Home (FAFH) prices reveals a 5.8% YOY increase¹. That’s a blended rate of what consumers pay for food and beverages that somebody else prepares for them. A 1% increase in a restaurant’s supply costs translates into roughly 0.33% higher COGS (at constant menu prices). A 12% increase therefore equates to ~4% higher COGS, nearly equivalent to an average FSR’s bottom line. The picture looks much the same with labor expense. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports that restaurant wages have risen 14.1% over the past year, so between the two Prime Cost components, the typical FSR has absorbed the equivalent of 8.5% of its revenues in the form of increased operating expenses. Those increased costs have yet to be fully passed along to consumers, leaving 350 basis points of operating margin unrealized and threatening the liquidity of thousands of operations.

Further injuring restaurant margins are the fixed expenses of rent, utilities, insurance, maintenance, and repairs, many of which have increased at a rate Pentallect estimates to be 2 – 4%. These, too, spell trouble for modest operators that struggle even during good times. But they also haunt stronger players that are hesitant to pass along the full extent of increased expenses in the form of higher menu prices for fear of chasing away customers to lower-cost alternatives. Higher labor costs favor more operationally efficient QSRs vs. “touch-intensive” and inefficient FSRs, an economic reality that will continue fueling consumer share shift from casual dining to fast casual and traditional fast food outlets. Pre-pandemic, spending at QSR and FSR venues was roughly equal, a ratio that shifted dramatically and continues today, reflecting concerns about the risks of indoor dining and QSRs relative strength in take-out and delivery.

The restaurant industry owes part of its success to a 30-year run of relatively benign ingredient and labor cost inflation, such that very few operators have experience coping with today’s circumstances. If, as many hope, the situation is “transitory,” the aggregate damage may be limited. At Pentallect, we think too many macroeconomic factors detract from “hope” being a viable strategy.

Gradually rising prices, wages, and GDP only occur when myriad market forces strike a rare and harmonious balance. The progression of the last 30 years (crises notwithstanding) is unprecedented in US history, a product of policy and technological advancements, demographics, and generally good luck. Productivity gains outpacing population and wage growth have fueled previously unimaginable wealth creation, quintupling over the timespan.

We remind ourselves that Americans spend the world’s lowest share of their Disposable Personal Income (DPI) on food and beverage while simultaneously spending half of that away from home, neither of which reflects an indulgent or cooking-averse populace. Rather, it’s a phenomenon uniquely supported by the world’s most productive agro-industrial complex, including the ~10% of working Americans staffing foodservice outlets at wages 50% below the national mean (an average they collectively reduce).

Labor shortages were widespread leading up to 2020 and amplified by COVID-19’s effects. In its wake, millions of workers seemingly left the foodservice industry and moved to other careers. Accelerated retirement rates among Gen-X and Boomers opened up opportunities for younger workers, triggering a “trickle-up” effect that reached deep into the labor “food chain,” as reflected in foodservice wages increasing at nearly triple the recent national “all jobs” average of 4.9%. Disproportionate foodservice pay increases will continue until equilibrium is reached, impacting the restaurant industry as expenses get passed through.

Relatedly, food processing workers are not much better paid than restaurant employees, a fact reflected in manufacturer staffing and production shortages. These job types also seek a balance between supply and demand that includes better wages, benefits, and working conditions that translate to higher prices across the ecosystem. Add firmly higher logistics costs to the mix and you will discover a recipe for 2-3 more years of elevated food and beverage price inflation. To be fair, shortage-driven price spikes should mitigate as firms get back to capacity, but cost baselines will have risen permanently.

So where does this all shake out? Seated dining, a luxury that grew mainstream over decades of American productivity and disposable income growth, may very well return to its roots – primarily serving consumers able to rationalize paying for the increased costs of serving them. The change will be gradual, but given time, will greatly influence the size and structure of the foodservice industry.

¹USDA reports Food At Home prices were +5.4% during the same time period.

By: Barry Friends | Bob Goldin